- What are you reading?

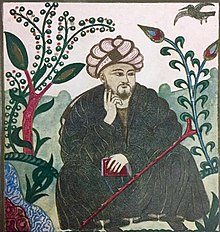

- About Al-Farabi, a 10th century Arabic philosopher.

- I thought you didn’t like Arabs.

- I don’t like terrorism.

- What do you like about the Arab?

- His interpretation of Plato. What I’m reading is by Leo Strauss, a German Jewish professor who taught at the University of Chicago. I was surprised I could find it on the internet. It's still in copyright, from 1945 I think. Found it on a peer-to-peer file sharing site, first time I used one.

- Why are you reading it? What is it about?

- How politics depends on religion, does now and always has.

My wife is skeptical.

Religion tells of an experience of wholeness, gratitude, security. It is the record of our awareness of these things.

There are two kinds of awareness. The kind that is produced by rituals, traditions, words repeatedly reflected upon. This is local, tied to time and place. And there is the philosopher’s understanding of life, that gives the same experience of security and comfort and gratitude. But the philosopher’s experience differs in that he knows how he got there, can tell a story of how security was betrayed and he made a return from out of confusion, and knows this history is more or less arbitrary: he could have got there thinking on different subjects in different ways. Reaching understanding is good in itself.

Now this is not just something abstract. I was at a cafe reading a book by one of Leo Stauss' students, Giants and Dwarfs, Allan Bloom’s essays about our time’s “value judgment” relativism, when a man asked if I’d mind if he sat down at my table. It turned out he was a professor of Black Studies. Might as well have told me he was a professor of relativism. I put the book away, and got right down to it: did he believe that a rap song was as good as Plato or Shakespeare? He said that one particular group’s songs were not only as good, but better. Why? Because they speak more to their audience, which was huge, and about things most important to them.

- But these songs can’t possibly do what Shakespeare and Plato did, describe many types of character and ways of life, living under different kinds of governments, show how they affected each other in ways good and bad, show the results of good character and bad.

- What he considered good and bad was what was in his times thought to be good and bad.

- And the rap singers know better? That is where we disagree: the reason these writers took for themselves such a large world of lives and characters to describe was to show that there was something in common between people, something good that could be kept or lost, depending on what happened between them in their lives. What the rap songs describe is only one kind of life.

- You are wrong: the songs tell stories, sometimes very complicated ones.

- Not in a way that you can see there is something good outside of what is politically good for one’s own group. Or am I wrong: you don’t believe in common human nature, and that art can be better or worse in bringing it out? That for example in Shakespeare and Plato there is truth that will always be true?

- No I don’t believe that. You say there is, I say there isn’t. Who decides?

- My decision is easier when I notice that conversation that never gets past thinking of what is good for one’s group is unpleasant and unenlightening.

On that note of unpleasantness the professor of Black Studies tells me he has work to do and the conversation ends.

The local religion has its local divinity, in this case it is race. The god of race is protected against competition from other local gods, and there is no other kind acknowledged than local.

The local religions are in conflict with each other, and also with the ideas that are the basis of democratic government. Democratic laws reflect a need to protect people from each other, rather than establish a society that is good in itself, that is beautiful, that is divine. Which is to say, life established under these laws does not produce the kind of secure, rewarding experience that is called religious. The laws give us the security in which we can have these local experiences.

But this is not exactly true. The laws of our democracies were the product of philosophers, who were readers of the very books dismissed as outdated by defenders of local religions. Those books taught the reason for and the necessity of the politeness and courtesies of public life. The gestures can often can be no more than an imitation of kindness, but that imitation serves as a reminder of the ever present possibility of sympathy with strangers, and a reminder often is all it takes if people haven't become too corrupt.

There is a divinity in these public manners, there is knowledge of human possibility in them higher than any art that is the product of any local tradition. Jefferson said that if a nation expects to be ignorant and free, it expects what never was and what never will be.

The conflict between the local and general divinities is an inherent problem for our politics. Forgotten by us, it was already known by Plato in the beginnings of our civilization. Strauss discovered it was still known by al-Farabi in the 10th century. In a safe society the local religious factions need the philosophers to keep them from killing each other, but cannot explain to themselves why this is so. They have to feel it. Which means they have to have already experienced it in part, and feel it strongly enough to want more of it.

Our leaders can take us to war for reasons of empire, to serve various factions religious or economic, and on spurious pretexts, and say they do this for the establishment of a new democracy. And they may not be lying. Just because they serve their local gods does not mean they don't also, perhaps inadvertently, serve also the public god, what Jefferson called Nature’s god.

P.S. What nobody wants to hear? We can't live on terms of equality with each other unless there have been people better than us.

No comments:

Post a Comment